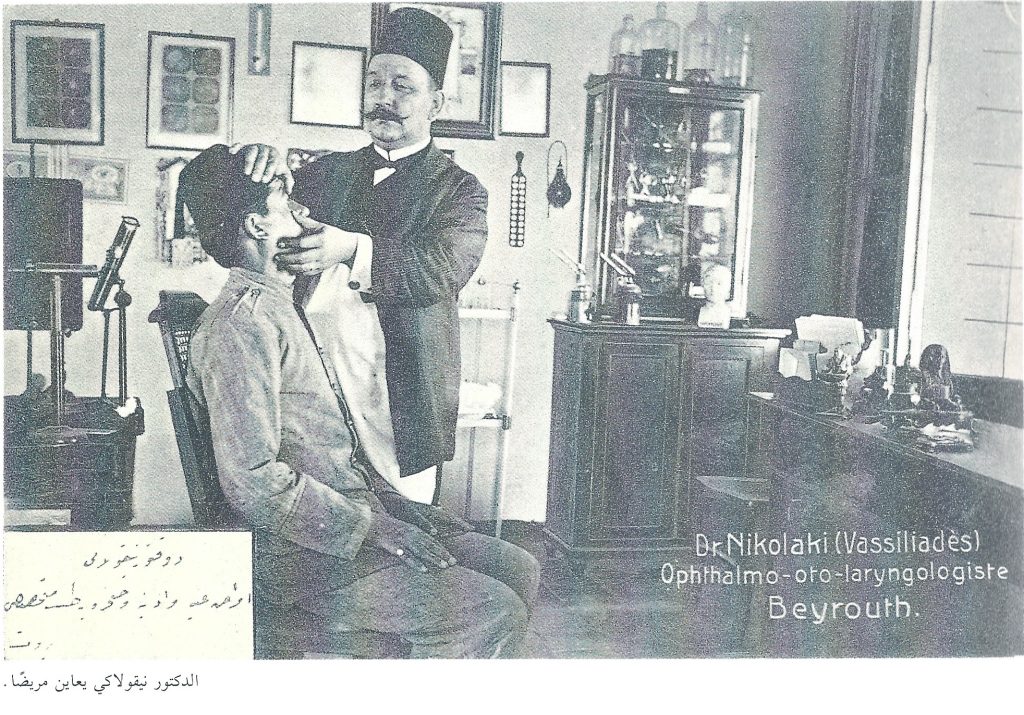

Ophthalmologist-laryngolist Dr Nikola Laki (Vassiliades) treats a patient at his clinic near Damascus Road, Beirut. Undated, the photo was probably taken sometime between 1910 and 1925. The early twentieth century was a period of transition from Ottoman to French rule in Beirut. It was also a time when the professions and professional institutions were consolidating their jurisdictional authority. Nineteenth century colonial visual culture had amassed a significant photographic archive and a set of cultural practices that continued to shape social, cultural, economic and political life. But how did local agency shape the visual archive of early twentieth century Beirut?

‘Scenes & Types’: Colonial Postcards and Photography in the C19th MENA region

There are many sub-genres within colonial visual cultures. “Scenes and Types” is a particularly distinctive one that correlates to the colonial production of knowledge and social space in the nineteenth century in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Scenes included landscapes, landmarks, buildings and monuments, many built by the colonisers, while types represented colonised people often in what was labeled ‘traditional dress’.

These visual props communicated the imperial project not only through the images they captured , but through their circulation in the postcard economy of the newly internationalising postal system of the nineteenth century. Colonised people were ‘typified’, often through the performance of dress and appearance by paid ‘actors’. Colonial ethnographic photography fabricated the foreign and exotic, and oftentimes the erotic as well, and domesticated it into a typology of categories through which knowledge about colonised people was produced and circulated as a form of power.

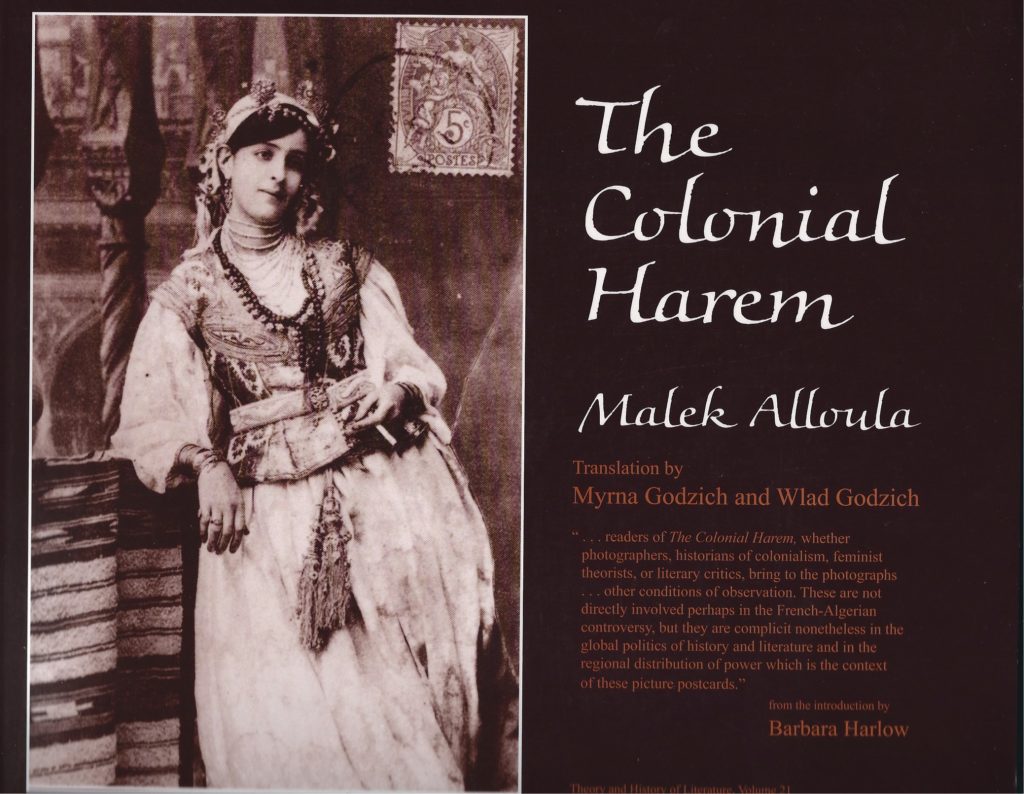

Women were particular targets. Malek Alloula’s study The Colonial Harem (1986) presents some of the ‘types’ that circulated through colonial postcards of Algeria. Postcards, marking out ‘the territorial spread of the colonist’ by being simultaneiously ‘at the scene of the crime’ (in the colonies) and ‘at a far remove’ (in the metropolitan centres) are described by Alloula as forms of symbolic violence: ‘the comic strip of colonial morality’ (Alloula 1986, pp.4-5). The catalogue of ‘types’ that can be found in the postcards and photographs reproduced within Alloula’s book is elaborate, with multiple subcategories, including: ‘Arab Woman’, ‘Woman from the South’, ‘Young Woman from the South’, ‘Bedouin Woman’, ‘Young Bedouin Woman’, ‘Kabyl Woman’, ‘Young Kabyl Woman’, ‘Young Moorish Woman’, ‘Moorish Woman’ and ‘Uled-Nayl Woman’. ‘Types’ also produced ‘groups’ and ‘practices’ like ”Group of Moorish Women in their Quarters’, ‘Family in front of their house’, ‘Native Family’, ‘Moorish Family’ or ‘Moorish Woman smoking a hookah’ and ‘Arab Woman having coffee’.

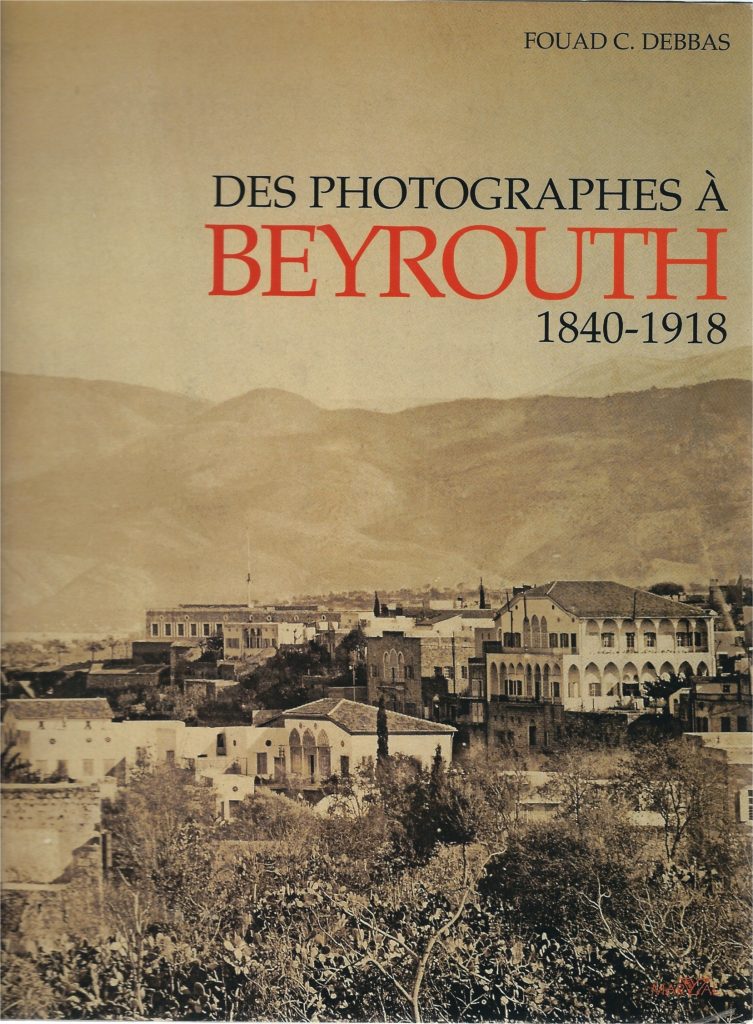

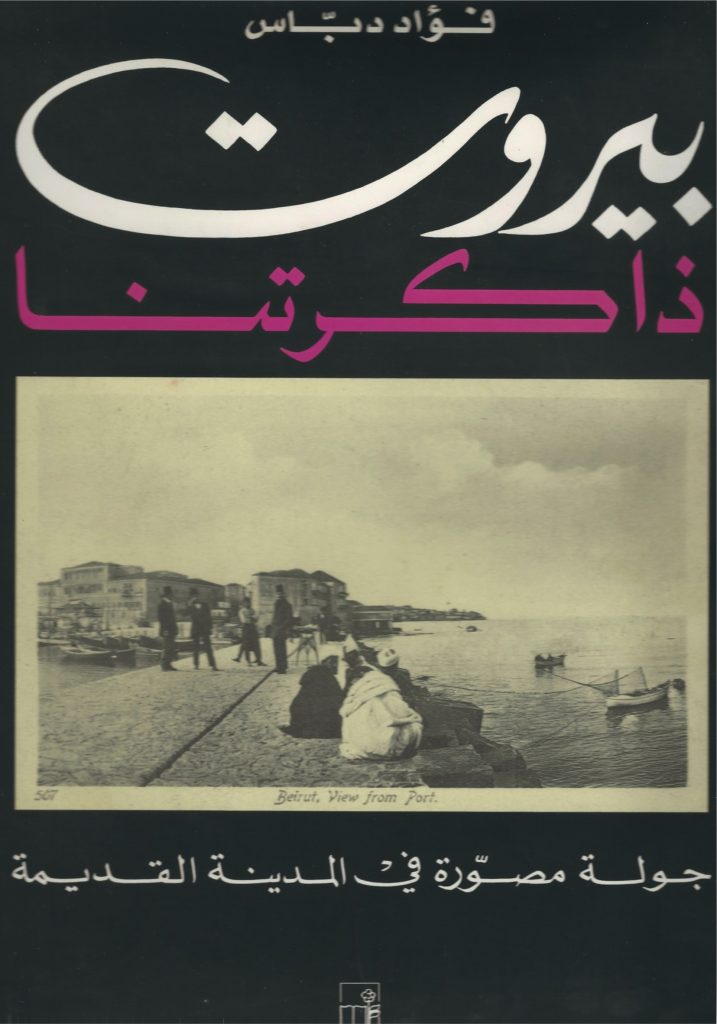

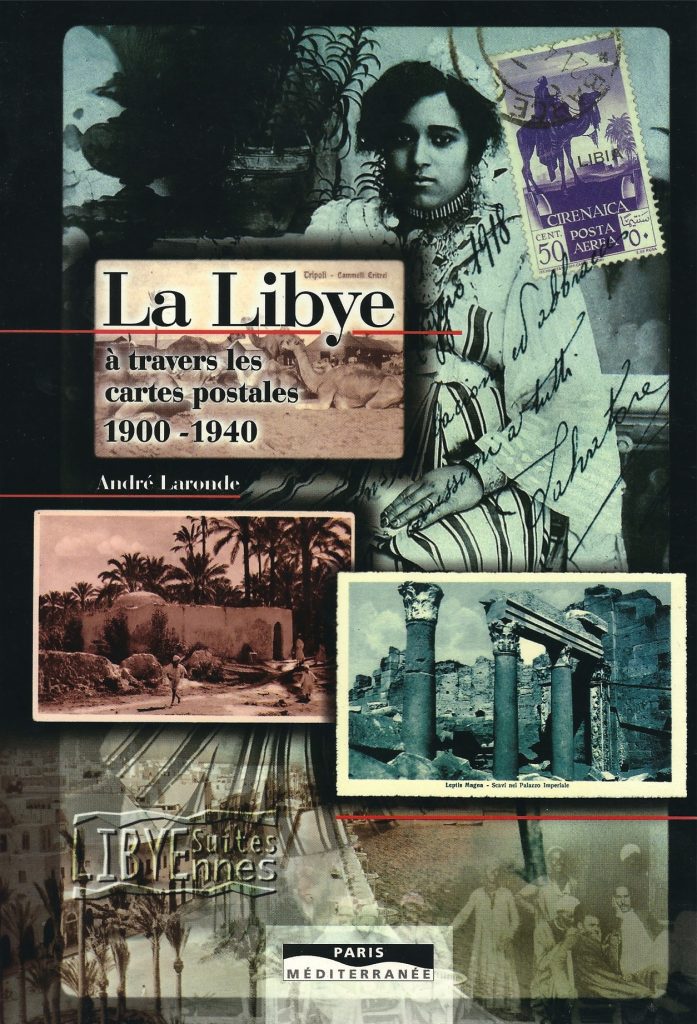

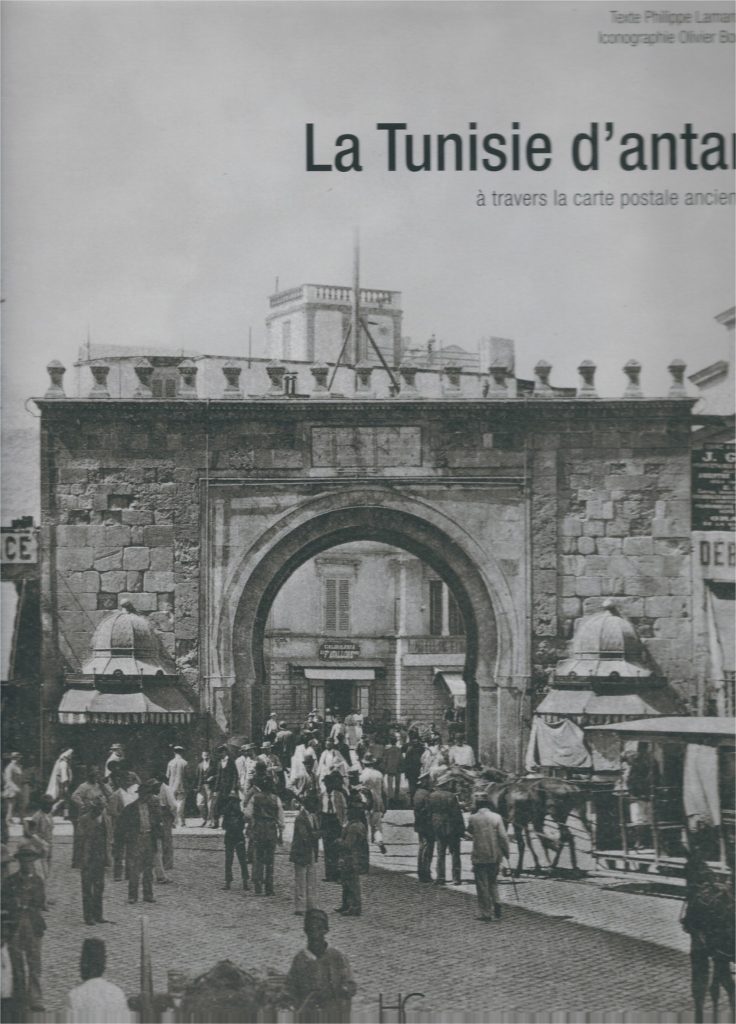

While Alloula’s study is perhaps the most well-known critical cultural deconstruction of ethnographic photography and colonial postcard culture, artefacts of empire continue to circulate today in numerous uncritical ways either as individual prints or postcards for purchase, or in collections of colonial photography. Numerous volumes on North Africa reproduce photographic catalogues that capture the minutiae of life from street scenes, desert scenes, public buildings, troop movements, panoramas, ‘traditional’ residential quarters, mosques, cafes, ports and ships, and ‘modern’ parts of the cities. These volumes also reproduce the familiar categories of ‘types’. The reproduction of the same ‘types’ across different colonial administrations demonstrates the work of typology in domesticating the images for a European audience. Postcards of Libya under Italian occupation, for example, share multiple similarities with those of French administered Algeria and Tunisia. The categories of ‘types’ are almost identical in both archives except for the regional and linguistic differences, with the Italian use of ‘tipi berberi’, ‘tripolino’ and ‘arabo’. The Levant had its own distinct categories: Bedouin, Shiite, Sunni, Druze and Christian. The typological images often depicted women, families or groups in the same manner as that of colonial visual culture in North Africa. Colonial visual culture in the nineteenth century Levant was produced by photographers like the Bonfils family and other Europeans. Many of these photographs are now archived at the American University of Beirut and reproduced in various catalogues (see for example Boraïe et.al. 2000 and Debbas 1994, 2001).

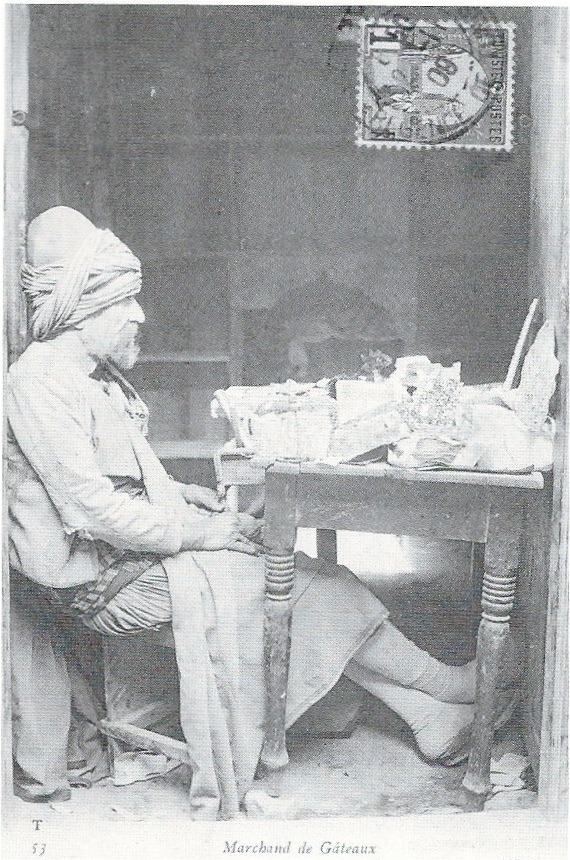

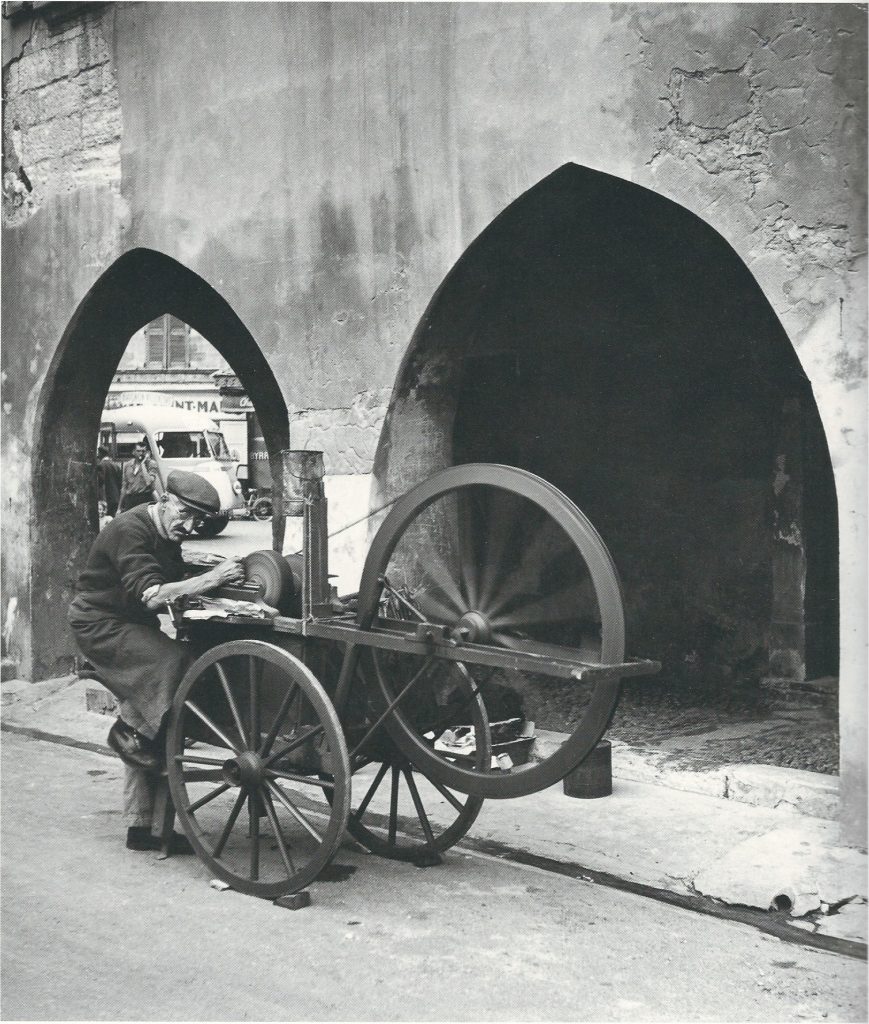

The categorisation of gender, race, ethnicity and religion in the production of ‘types’ constitute the stereotypes of the Orient exposed so powerfully by Edward Said in Orientalism. But colonial visual culture also produced new practices of performance around the body and ways of interacting and constructing urban social space. Another well-known sub-genre is ‘les petits métiers’, or the photographic representations of artisan street merchants. Popularised in the European metropolises by photographers like Eugene Atget in the twentieth century, the sub-genre had long been in circulation in the colonies. ‘Les petits métiers’ showed images of artisans and street merchants at work, at once testifying to the social production of urban space through labour, but also, as often expressed by the photographers, documenting an era at the moment of its disintegration as modern technologies and the expansion of international capital were displacing many street traders from the urban circuits of labour.

Professions and Institutions: Beirut in the C20th

As photography became well established in the MENA region in the early twentieth century, it proliferated its own practices, many of which challenged the typological repertoires of colonial visual culture. Women who could afford to do so often sought the services of a professional photographer who would photograph them wearing ‘Western attire’ and produce a portfolio of prints for their own private use. ‘Photo surprise’ became a popular genre in the MENA region. Photographers would stand on street corners and take images as pedestrians walked by. Once the scene was captured on film, the passers-by would be given the details of the photographer’s studio where they could pay for, and collect, their images. Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari have documented and written about these practices. They say: ‘We proceed from the thesis that the photographic practices in question are symptomatic of an evolving capitalist organisation of labour and its products, and of established conventions of iconic representation. We also propose that these practices were not only reflective but also productive of new notions of work, leisure, play, citizenship, community and individuality’ (in Bassil et.al. 2005). For more of their work see the collection of the Arab Image Foundation.

The intersection of colonial visual culture and everyday life, of an evolving capitalist economy and its attendant labour practices, amassed a historical archive that could be exploited by the colonial project. But as Bassil and others note, the production of visual culture also redefined local notions of self, work, and community. The proliferation of local producers and participants in the production of this archive requires us to think differently about the ways in which local agents contributed to it, and the terms under which they participated. These contributions also need to be considered in light of the historical junctures at which they were produced and the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic notions of visual representation and broader social, culture and political ideas operating at that juncture.

Opthamologist and laryngologist Dr Nikola Laki (Vassiliades) poses with a patient at his clinic in the Damascus Road (Tariq Al-sham) area of Beirut (see photo above). The area was known for its specialist medical practitioners, hospitals and medical education facilities. In the photo of the doctor and his patient, both men are dressed in pants, shirts and jackets, with the doctor wearing a bow-tie. The office is well-furnished and appears to be equipped with the most up-to-date equipment and facilities. Both men are also wearing the fez, indicating the photo (undated) was most likely taken before the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, or just after it. Another photo of a group of male students standing outside the entrance of the nearby French Faculty of Medicine shows the hegemony of the Western style suit at that particular time. The photo is dated from 1920. It also attests to shifts underway after the demise of the Ottoman Empire in the style of headgear for men, with both the fez and the bowler hat present.

As visual records of the evolution of medical knowledge and practices in the former Ottoman province of Beirut during the period of the Empire’s disintegration and/or the Mandate period, the photographs raise a number of questions about their production within the broader colonial economy. Were they produced specifically for utilisation as exemplary cases in the French colonial project? Were they taken by a local photographer a travelling French photographer? The photographs also raise a number of questions about the participants and their agency in the production of these photos. In what ways does their participation reflect or reshape local notions of medical practice and education? To what extent do they see themselves, and act within their capacity, as agents of modernity? Finally, we might also ask how the visual documentation of the professions and their institutions in the early twentieth century intersects with the representation of merchants and street traders in ‘Les petits métiers‘ genre, and more broadly with the ethnographic framework of the ‘Scenes and Types’ genre.

Beirut in the early 1920s, like much of the rest of the world, was a place of transition. Power had shifted from the Ottomans to the French after WWI, and nationalist political movements were on the rise. The early 1920s is also a time when globally, the professions were fighting for and claiming jurisdiction and authority within the globalising world economy. Not just the doctors, but also the photographers. Social and cultural practices were changing, and political thought was already challenging French rule. And all this at a time when the majority of the city’s population had probably not yet visited a modern medical facility.

To cite this blog post: Dados, N (2019), ‘Scenes and Types’. Notes in Precaria Blog. Originally published 14 August, 2019.

Title photo: ‘Nalut: tipi berberi’ in Laronde, A. (1997) La Libye: à travers les cartes postales 1900-1940. (Tunis: Les Editions de la Méditerranée).

References:

Alloula, M. (1986) The Colonial Harem. (Minneeapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press; translated by Godzich, M. & Godzich, W.)

Bassil, K., Maasri, Z. & Zaatari, A. (2005) Mapping Sitting: On Portraiture and Photography. (Beirut: Mind the Gap and Arab Image Foundation; 2nd edition).

Boraïe, S., Haller, D.M., & Pezzati, A. (2000) In Arab Lands: The Bonfils Collection. (Cairo: The American University of Cairo Press).

Debbas, F.C. (2001) Des Photographes à Beyrouth 1840-1918. (Paris: Marval)

Debbas, F.C. (1994) Bayrut: Dhakiritna (Beirut our Memory). (Beirut: Beysat).

Favrod, C. (2005) Le temps des colonies. (Lausanne and Paris: Favre).

Lamarque, P. & Bouze, O. (2011) L’Algerie d’antan à travers le carte postale ancienne. (Paris: Éditions Hervé Chopin; 2nd edition).

Lamarque, P. & Bouze, O. (2011) La Tunisie d’antan à travers le carte postale ancienne. (Paris: Éditions Hervé Chopin; 2nd edition).

Laronde, A. (1997) La Libye: à travers les cartes postales 1900-1940. (Tunis: Les Editions de la Méditerranée).

Le Feuvre, L. & Zaatari, A. (2004) Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices. (Beirut: Mind the Gap and Arab Image Foundation).

Perret, P. (2007) Les petits métiers d’Atget à Willy Ronis. (Paris: Éditions Hoëbeke).

Notes in Precaria ©2018-2023 Niki Dados